Freedom is something that most of us take for granted. Even today, as we wake up and go wherever we want to, or need to, go, there are millions of people in the world who cannot. Many of them are literally slaves – working long, tortuous hours, in inhumane conditions, beaten into submission, for no money.

Slavery in America was considered ‘legal’ from 1619 – when the country was still a group of English colonies – until the Thirteenth Amendment was passed in 1865. Most of the slaves – men, women and children – were of African descent and ‘owned’ by White masters to live on their plantations and work their crops of tobacco, cotton, sugar, and coffee. By the early decades of the 19th century, the overwhelming majority of slaveholders and slaves were in the Southern United States. By the Civil War, most slaves were held in the Deep South.

It was literally back-breaking – and sometimes soul-destroying – work; and many slaves would do anything to break the chains of servitude.

|

| Slaves in a Cotton Field |

Before Abraham Lincoln signed The Emancipation Proclamation in 1865, following The Civil War, some slaves – mostly in Northern States – were either given their freedom, or were able to purchase it. Also, most States in The North had already outlawed slavery – making them ‘free’ States. Much of this organized split between the States was initially due to the Missouri Compromise, which was an agreement passed in 1820, between the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in the United States Congress, involving primarily the regulation of slavery in the western territories. It prohibited slavery in the former Louisiana Territory, except within the boundaries of the proposed State of Missouri.

For those slaves who were not free, many tried to escape. Many were unsuccessful and greatly suffered upon recapture. However, over 100,000 who were successful; with the help of Black and White Abolitionists and most often following harrowing journeys on ‘The Underground Railroad’ – a network of secret routes and safe houses, to escape to free States, Canada, Mexico and overseas, with the aid of abolitionists and allies, who were sympathetic to the slaves’ cause.

Legend has it that, in 1831, Tice Davids, a runaway slave, fled from his owner in Kentucky. Tice swam across the Ohio River, with his owner in close pursuit in a boat. Tice reached the Ohio shore just a few minutes before his owner, but his owner could not find him and at first thought, perhaps Tice had drowned, but later, admitted that he had simply vanished, saying that Tice, "must of gone off on an underground road." It is thought that local abolitionists hid Tice and helped him escape. Rush Sloane, an Ohio abolitionist, claimed that this led to the naming of the Underground Railroad. Historians continue to remain divided as to the accuracy of this statement. Nevertheless, the Underground Railroad definitely existed; and it was at its busiest between 1850 and 1860, when more than 30,000 slaves escaped, during that decade.

In both 1793 and 1850, The Fugitive Slave Law and The Fugitive Slave Act were passed, respectively, requiring that escaped slaves be returned to their masters and giving legal authority to the slave-catchers – even in free States. Abolitionists nicknamed the 1850 Act ‘The Bloodhound Law’, after the dogs, which were used to hunt the escaped slaves.

|

| Hunting an Escaped Slave |

The Fugitive Act of 1850 did not just apply to runaway slaves. Because strong, healthy blacks in their prime working and reproductive years were seen and treated as highly valuable commodities, it was not unusual for Free Black people to be kidnapped and sold into slavery. "Certificates of Freedom"—signed, notarized statements attesting to the free status of individual Blacks—could easily be destroyed and thus afforded their holders little protection.

|

| Certificate of Freedom |

Under the terms of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, when suspected fugitives were seized and brought to a special magistrate known as a commissioner, they had no right to a jury trial and could not testify in their own behalf. Technically, they were guilty of no crime. The marshal or private slave-catcher needed only to swear an oath to acquire a writ of replevin for the return of property.

Despite those laws, the Underground Railroad thrived. The escape network was not underground, nor was it a railroad. It was figuratively "underground" in the sense of being an underground resistance. The Underground Railroad consisted of meeting points, secret routes, transportation, and safe houses, and assistance provided by abolitionist sympathizers. Individuals were often organized in small, independent groups; this helped to maintain secrecy because individuals knew some connecting ‘stations’ or ‘depots’ along the route, but knew few details of their immediate area. Escaped slaves would move North along the route from one way station to the next; and the routes were often purposely indirect to confuse pursuers. "Conductors" on the railroad came from various backgrounds and included free-born Black people, White abolitionists, former slaves, and Native Americans. The stations consisted of homes, churches, barns, shops and shacks.

|

| Underground Railroad Station - Church |

The Black conductors would sometimes pretend to be a slave to enter a plantation. After having infiltrated the plantation, the conductor would direct the runaways to the North. Slaves would travel at night, about 10–20 miles to each station – mostly on foot or in a false-bottom wagon – sometimes by boat or train.

|

| Runaway Slaves |

|

| False-Bottom Wagon |

The Big Dipper (whose "bowl" points to the North Star) was known as the Drinkin' Gourd, and was used to guide the slaves. They would stop and rest during the day, at the stations, hidden away in secret rooms and under bales of hay.

|

| Hidden Room in the Bedroom of an Underground Railroad Station |

While resting at one station, a message was sent to the next station to let the station master know the runaways were on their way. The messages were often encoded so that could only be understood by those active in the railroad. For example, the following message, "I have sent via at two o'clock four large hams and two small hams", indicated that four adults and two children were sent from Harrisburg to Philadelphia, on the 2pm Train.

There is also a theory that quilts were used to signal and direct slaves to escape routes and assistance. According to the ‘quilt theory advocates’, there were ten quilt patterns that were used to direct slaves to take particular actions. The quilts were placed one at a time on a fence or a window ledge, as a means of nonverbal communication to alert escaping slaves. The code had a dual meaning: first to signal slaves to prepare to escape and second to give clues and indicate directions on the journey. Some quilt experts dispute this theory.

|

| Underground Railroad Station Quilt |

Yet another theory about how the encoded messages were delivered was through Negro Spirituals, such as “Steal Away” and "Follow the Drinking Gourd," whose coded information helped the escaped slaves to navigate The Underground Railroad. However, scholars dispute the theory, and have proposed that while the songs may certainly have expressed hope for deliverance from the slaves’ sorrows, they did not present literal help for runaway slaves. Click here to see and hear a 1957 recording of Mahalia Jackson and Nat King Cole singing Steal Away.

|

| Nat King Cole and Mahalia Jackson |

Whether the disputed claims are actually true or not, has gone with the runaways slaves and abolitionists to their graves.

All of those involved in The Underground Railroad risked everything for freedom. The slaves were hunted down by any means necessary, and rewards were put on their heads, because as far as the slave masters were concerned, they had lost their property – Property, which made them money. Southern newspapers of the day were often filled with pages of notices soliciting information about escaped slaves and offering sizable rewards for their capture and return.

There were many people who helped the slaves to freedom. Some of the notable ones were:

JERMAIN LOGUEN, a fugitive, son of his Tennessee slave master and a slave woman, who helped 1,500 escapees and started Black schools in New York State;

|

| Jermain Loguen |

JOHN GREENLEAF WHITTIER, a Quaker poet who gave a powerful voice to the abolition movement;

ALLAN PINKERTON, a Scottish immigrant who managed an underground depot at his cooper’s shop near Chicago, before starting his now-famous Pinkerton security firm;

|

| Allan Pinkerton |

JOSIAH HENSON, a Black slave overseer, who subsequently became an escaped slave who ran to Canada, and helped others to escape;

|

| Josiah Henson |

THOMAS GARRETT, a Wilmington, Delaware businessman who aided more than 2,700 slaves to freedom;

MARY ANN SHADD, the daughter of a Black agent in the Wilmington, Delaware Underground Railroad;

|

| Mary Ann Shadd |

WILLIAM LLOYD GARRISON, one of the earliest, most passionate abolitionists, who spent all of his time speaking out against slavery;

JONATHAN WALKER, who was imprisoned for helping seven slaves sail from Florida, bound for the Bahamas, and branded on the hand with SS for “Slave Stealer;”

|

| Jonathan Walker's Branded 'Slave Stealer' Hand |

LEVI COFFIN, a Quaker, abolitionist, and businessman, who was deeply involved in the Underground Railroad in Indiana and Ohio and his home, in Indiana, was often called the "Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad". He was nicknamed "President of the Underground Railroad" because of the 3,000+ slaves that are reported to have passed through his care while escaping their masters;

|

| Levi Coffin's House |

JOHN FAIRFIELD, who was born to a slave-holding family in Virginia, but disagreed with his family's livelihood as he became a young man. When he was twenty, he helped a childhood friend escape from his uncle's farm taking him to Ohio. During the 1850s, he quickly established himself with a reputation as one of the most cunning conductors on the Underground Railroad and specialized in reuniting broken families;

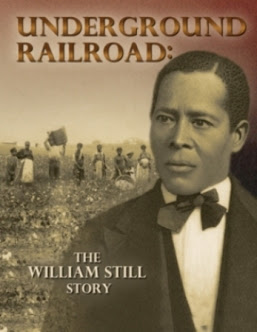

WILLIAM STILL, often called "The Father of the Underground Railroad", who helped hundreds of slaves to escape (as many as 60 a month), and kept careful records, including short biographies of the escapees and maintained correspondence with them, eventually turning his memoirs into a book, The Underground Railroad in 1872;

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, a fugitive slave, who became a skilled abolitionist speaker, praised for “wit, argument, sarcasm, and pathos,” and urged Black people to pursue vocational education and the vote. His print shop in Rochester, New York, was a depot on the Underground Railroad; and

HARRIET TUBMAN, an escaped slave, herself, who made 19 trips into the South and escorted over 300 slaves to freedom. William Still, in his book, described Harriet her as "a woman of no pretension, a most ordinary specimen of humanity." Pauline Hopkins, noted Black author around the turn of the century, eulogized Tubman as follows: "Harriet Tubman, though one of the earth's lowliest ones, displayed an amount of heroism in her character rarely possessed by those of any station in life. Her name deserves to be handed down to posterity side by side with those of Grace Darling, Joan of Arc and Florence Nightingale; no one of them has shown more courage and power of endurance in facing danger and death to relieve human suffering than this woman in her successful and heroic endeavors to reach and save all whom she might of her oppressed people."

|

| Harriet Tubman |

All of these abolitionists – named and unnamed – free and bonded – never took ‘freedom’ for granted. If it were not for them, who knows what Black History would look like today?

Common travel food for the runaway slaves included: roasted sweet and white potatoes, jerked beef, fruit and cornbread. Here is a simple, delicious recipe for Honey Cornbread Muffins. Enjoy!

Honey Cornbread Muffins

By Pat & Gina Neely, Down Home with the Neelys, Food Network

Recipe converter here: http://southernfood.about.com/library/info/blconv.htm

Ingredients:

- 1 cup yellow cornmeal

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- 1 tablespoon baking powder

- ½ cup granulated sugar

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 cup whole milk

- 2 large eggs

- ½ stick butter, melted

- ¼ cup honey

Special equipment: paper muffin cups and a 12-cup muffin tin

Preparation:

Preheat oven to 400 degrees F.

Into a large bowl, mix the cornmeal, flour, baking powder, sugar, and salt. In another bowl, whisk together the whole milk, eggs, butter, and honey. Add the wet to the dry ingredients and stir until just mixed.

Place muffin paper liners in a 12-cup muffin tin. Evenly divide the cornbread mixture into the papers. Bake for 15 minutes, until golden.

SOURCES: Wikipedia, National Geographic, The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center Ohio

SUSAN B. ANTHONY, a Quaker schoolteacher, who spoke out for temperance, women’s rights, and abolition, who later led the fight for women’s suffrage;

No comments:

Post a Comment